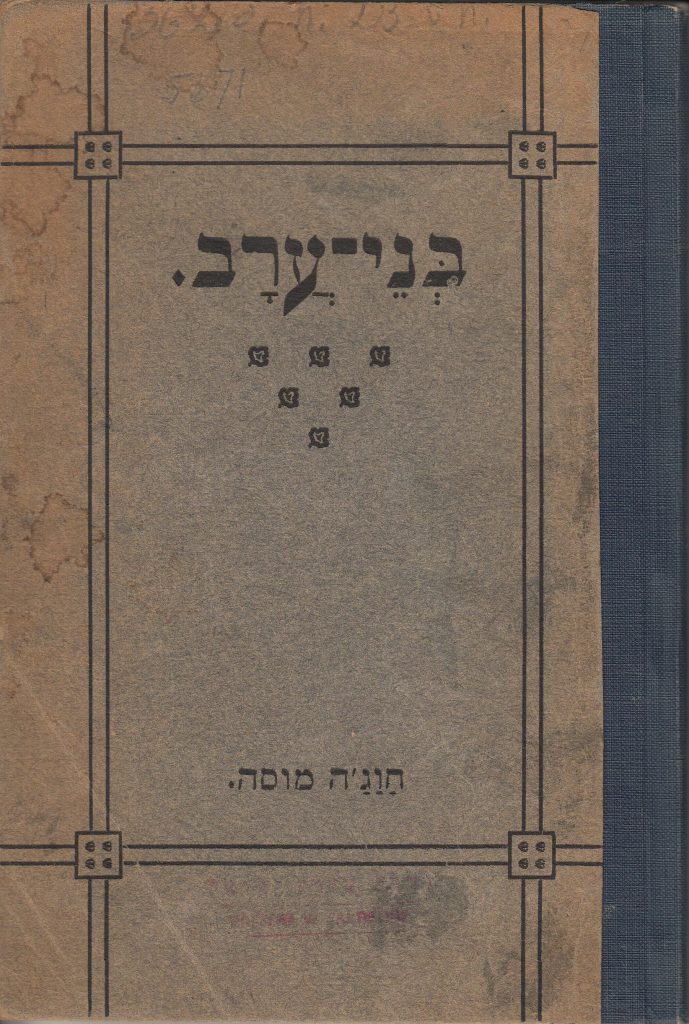

Moshe Smilansky first published bney arav as a single volume of 19 short stories featuring Arab characters in 1911 under the pseudonym Khawaja Musa. After WWI, he expanded it to 51 stories and it has subsequently appeared as two volumes in editions of his collected works.

The Hebrew title bney arav is a parallel to the biblical bney yisrael “sons of Israel,” which is translated in the King James Version as both “children of Israel” and “Israelites”.

So the title bney arav might be translated literally as “Sons of Arabs” or “Children of Arabia.” Perhaps the older term “Araby” is preferable in English since it avoids conveying “Arabs” as individuals or “Arabia” as a geographical location. And “sons of Araby” is possibly preferable to “children” here since unlike “children of Israel,” “children of Araby” is not a known term and risks sounding like something about small children.

In the book of Genesis, the name “Israel” was not the name of a place, but was another name given to the Jewish patriarch Jacob. So it makes sense that his descendants are bney yisrael “sons of Israel.” In the same way, the names of some Bedouin tribes begin with the word bani or banu which is equivalent to the Hebrew bney. So the Bani Hasan are literally the “sons of Hasan,” etc. Indeed, the children of Israel are bani isra’il in Arabic.

But in Arabic, Arabs in the plural are simply ‘arab. The Arabic equivalent of Smilansky’s title would be bani ‘arab which seems somewhat redundant. But its singular ibn ‘arab “son of the Arabs” may have a distinct meaning. In an interview in the early 1980s, member of Knesset Muhammed Wattad explains this term and also the term khawaja:

“Usually, when one says ibn ‘arab, the intention is to pay a compliment. ibn ‘arab means one of us, who knows how to act according to the rules and according to tradition… On the other hand, when one says about someone khawaja, that is to say that he is a stranger.” (From “These are the Tribes of Israel” by Sami Michael, 1984).

This is probably close to what Smilansky intended by titling his book bney arav. And it is probably close to what he intended by using the pseudonym Khawaja Musa. “Musa” is of course the Arabic name for Moses, as “Moshe” is in Hebrew. According to his grand-nephew Yizhar Smilansky (better known to the literary world as S. Yizhar), the elder Smilansky was indeed in his day addressed by local Arabs as Khawaja Musa, and this was for him a source of pride and satisfaction. It also suggests that while he was proud to have earned the Arabs’ respect, he did not, like T.E. Lawrence, aspire to be accepted as one of them or take up their cause. At the same time, he clearly saw some parallel between the bney arav of his own era and the bney yisrael of biblical times.

Smilansky was unusual in the extent of his interest in the local Arab population. Like other early Zionists, his main goal was the building of a Jewish homeland through the acquisition of land and its productive agricultural use. Another important goal was the revival of the Hebrew language, which was not his native language. Most of his other writing concerned Jews, and considering all of his other pursuits, agricultural, political, and military, it is amazing how much time he spent writing about Arabs and how vivid and detailed are his depictions of tribal and village life. Given that most Arabs were at the time illiterate, and given that literate Arabs at the time were more likely to be concerned with either religious or political purposes, it is doubtful if any Arab writer has ever left us with as intimate and dedicated a portrait of the lives of ordinary Arabs of that time. After WWI, the world would be turned inside out and upside down. Wars, revolutions, and violent upheaval would render Arab society almost unrecognizable, and this period would never be revisited except through a heavy haze of nostalgia, and never with the physical familiarity of a contemporary such as is the case with Smilansky. Presumably, the people he wrote about would be called “Palestinian” today, although it is doubtful many of them would have recognized this word at the time. On the other hand, most if not all were surely proud to be ibn ‘arab.

Arab life as described by Smilansky was hard. Non-urban Arabs were often sharecroppers or hired hands. They were often illiterate and innumerate and without political clout and were beheld to local chieftains and landowners. They were paid in kind, owed tithes to the landowners and taxes to the Ottoman government, and often were not able to feed and clothe themselves and their families. Their betters took advantage of their weakness to further dispossess and indebt them. Bedouin and Fallah alike were dependent on rain in the winter and crop failure meant mass starvation and the migration of entire villages and tribes to distant parts to beg and hire themselves out for food. Neither the government nor more fortunate villages or tribes were likely to offer charity. Beatings at the hands of the powerful were common, although murder was rare as that was likely to bring the government, who tended to be brutal and corrupt.

Marriages were arranged by fathers or male relatives who collected the bride price from the groom or the groom’s family. Due to polygamy by the wealthy, poorer men could often only afford to marry if at all after a lifetime of hard labor and deprivation to save up for the price of a bride. Girls who were orphans, or who ran away rather than marry the man who had paid their price, found themselves in a particularly compromised position.

What Arabs had that got them through the hardships they faced was their pride in being Arabs and their traditions, which were quite complicated. As Smilansky writes of one young Bedouin: “He had his own laws, oral laws that were more sanctified in his eyes than any written law… And in his Shulchan Aruch, arranged in all its details and particulars in his brain, he found clear answers to life’s questions.” And yet, Arab society itself was already changing rapidly due to the industrial revolution, the arrival of large numbers of Jews, and what many must have sensed was the imminent demise of the Ottoman Empire. All of these changes can be traced though the subplots of many of the stories. Some of the stories added in the expanded edition also mention WWI and the arrival of the British.

Smilansky was fascinated and drawn to the Arabs, even if he couldn’t condone everything they did or comprehend why they did it. They were wholly different from himself or anyone else he had known. They had a different way of thinking, a different way of reacting, a different way of seeing the world. He did not seek to emulate or even fully understand them. He sought to know them, when possible to befriend them, and he sought to convey in his writing as much as he could about them. Some of these stories are great short stories that can be enjoyed on multiple readings. Some are not as great. Some are disjointed or lack sufficient background or character development. Some are overly long and rambling. But every story expresses some unique insight by the author that fills out the complete portrait of the times and the people he sought to depict.

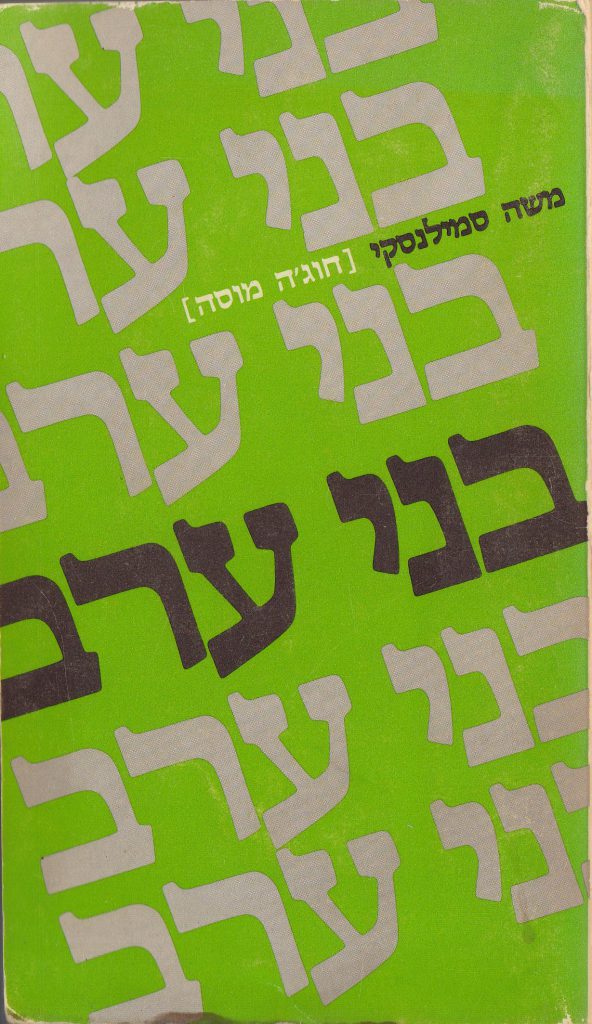

A single volume of eleven stories, containing seven stories from bney arav, was published in English in 1935 under the title Palestine Caravan (London: Methuen & Co.) and has never been reprinted. Even in Hebrew, Smilansky has fallen out of fashion. The last printed edition of bney arav was as part of an edition of Smilansky’s collected works published in 1964 (Tel Aviv: Dvir).